The Imperial Palace: travel station and residence in the Empire

A journey through time in the footsteps of Charlemagne: The museum in the imperial palace in Paderborn

At the Museum in the Imperial Palace in Paderborn, visitors can follow in the footsteps of Emperor Charlemagne. As a replica of the imperial palace itself, the museum is an attraction on its own and alongside the famous cathedral a magnet for visitors.

Watch the video on YouTubeWhat is an Imperial Palace?

The palace of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill is the origin of the term palace as palatium (Latin for vault). The magnificent buildings were visible signs of royal rule. Since the Carolingian period (8th century), kings were traveling rulers. They did not have a fixed capital or residence, but presented their power in as many places as possible in their territory. Most royal palaces, which were spread across the entire empire as temporary residences, were elongated hall or hall buildings until the Hohenstaufen period (11th to 13th century).

The kings resided in these palaces accompanied by members of their family, advisors, scribes, warriors and people who earned their living at and with the royal court. The royal party, which often comprised more than a hundred people, traveled on horseback or on foot and visited the palaces with varying frequency depending on their facilities and location. However, royal palaces also had a military function: from the late Carolingian period, they were often fortified by a solid wall or a wood-and-earth rampart.

An Imperial Palace in Paderborn

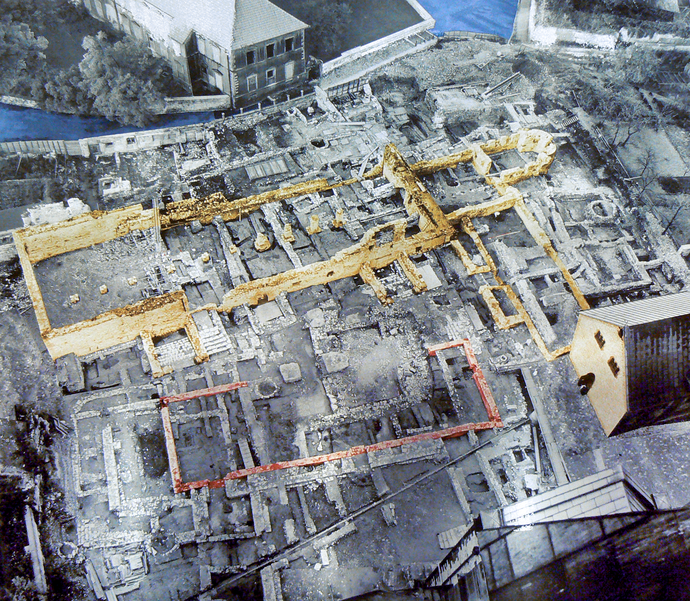

Experts had long suspected from historical records that Charlemagne had also left behind architectural traces of his immense power in Paderborn. However, there was no proof of this. Only an archway hinted at the possibility that a real sensation lay hidden beneath meters of rubble. When the cathedral chapter planned to redesign the area north of the cathedral in 1963, the archaeologists from the Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe first took a look in the ground.

It soon emerged that the walls that had come to light belonged to the remains of the palace that Bishop Meinwerk of Paderborn had built for King Henry II. A little later the sensation: even older walls emerged among the already sensational findings. Excavator Wilhelm Winkelmann had discovered Charlemagne's palace. The discovery triggered further research, which has long made Paderborn's town center one of the best-researched complexes of its kind in Europe.